The Importance of the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a turning point in the Pacific War. Before the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7-8 May 1942, the Imperial Navy of Japan had swept aside all of its enemies from the Pacific and Indian oceans. At the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese won a tactical victory, but suffered an operational-level defeat: it did not invade Port Moresby in New Guinea and set up a base from which its land-based planes could dominate the skies over northern Australia. However, the overall military initiative was still in the hands of the Japanese. Their carrier striking force was still the strongest mobile air unit in the Pacific, and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese fleet commander, hoped to use it to smash what remained of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet.

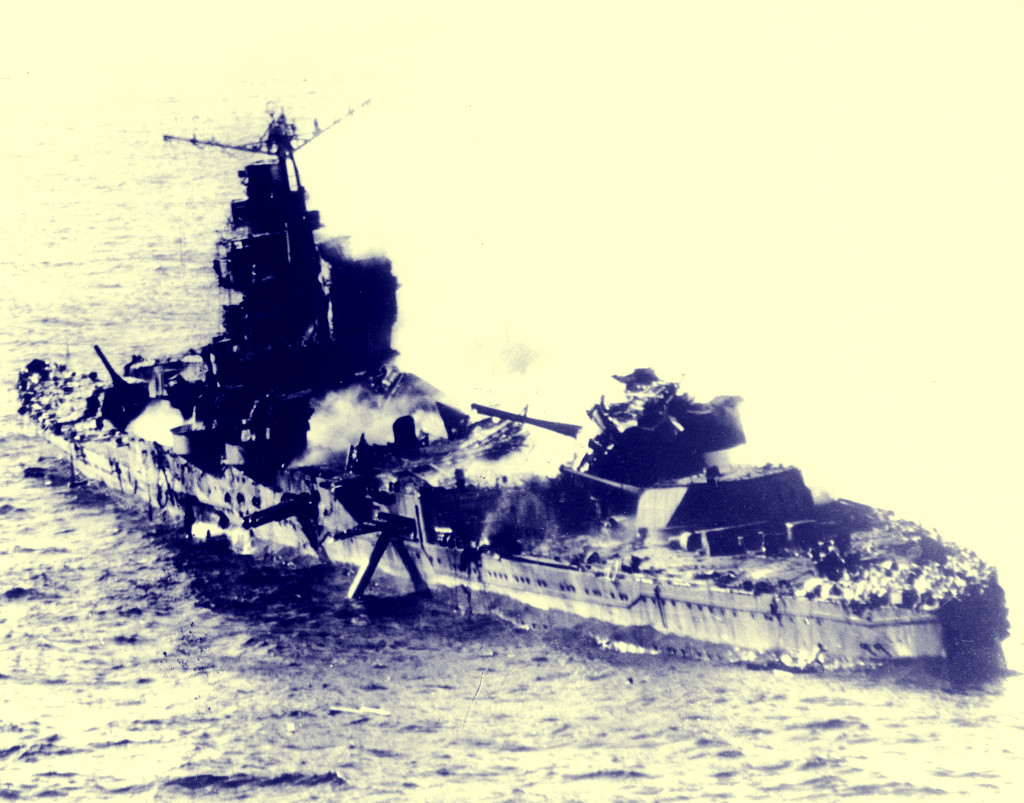

Yamamoto’s plan was to attack and then assault the two islands that make up the Midway atoll. He reasoned that the U.S. Navy could not tolerate such an operation so close to its base in Hawaii, and he believed—correctly, as it happened—that what was left of the U.S. Pacific Fleet would sortie from Pearl Harbor and expose itself to the power of his carrier force and his most powerful battleships. Yamamoto wanted his carriers, led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, to ambush any American carriers and surface ships that ventured to contest the Japanese attack and assault on Midway. Instead, he was ambushed by the three U.S. carriers—Yorktown, Enterprise, and Hornet—that had steamed north and west from Hawaii. In just one day—4 June 1942—Admiral Nagumo lost his four carriers to the air units of his American opponents, while U.S. naval forces lost only one carrier (Yorktown) in return.

Why was Midway such a critical victory? First, the fact that the U.S. Navy lost just one carrier at Midway meant that four carriers (Enterprise, Hornet, Saratoga, and Wasp) were available when the U.S. Navy went on the offensive during the Guadalcanal campaign that began the first week of August 1942. Second, the march of the Imperial Japanese Navy across the Pacific was halted at Midway and never restarted. After Midway, the Japanese would react to the Americans, and not the other way around. In the language of the Naval War College, the “operational initiative” had passed from the Japanese to the Americans. Third, the victory at Midway aided allied strategy worldwide.

That last point needs some explaining. To understand it, begin by putting yourself in the shoes of President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the beginning of May 1942. The military outlook across the world appears very bad for the Allies. The German army is smashing a Soviet offensive to regain Kharkov, and soon will begin a drive to grab the Soviet Union’s oil supplies in the Caucasus. A German and Italian force in North Africa is threatening the Suez Canal. The Japanese have seriously crippled the Pacific Fleet, driven Britain’s Royal Navy out of the Indian Ocean, and threaten to link up with the Germans in the Middle East.

If the Japanese and the Germans do link up, they will cut the British and American supply line through Iran to the Soviet Union, and they may pull the British and French colonies in the Middle East into the Axis orbit. If that happens, Britain may lose control of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Soviet Union may negotiate an armistice with Germany. Even worse, the Chinese, cut off from aid from the United States, may also negotiate a cease-fire with the Japanese. For Churchill, there is the added and dreaded prospect that the Japanese may spark a revolt that will take India from Britain. Something has to be done to stop the Japanese and force them to focus their naval and air forces in the Pacific—away from the Indian Ocean and (possibly) the Arabian Sea.

Midway saves the decision by the Americans and British to focus their major effort against Germany, and the American and British military staffs are free to plan their invasion of North Africa. The U.S. Navy and Marines also begin planning for an operation on Guadalcanal against the Japanese. As Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance—one of the Navy’s carrier task force commanders at Midway—put it after the battle, “We had not been defeated by these superior Japanese forces. Midway to us at the time meant that here is where we start from, here is where we really jump off in a hard, bitter war against the Japanese.” Note his words: “… here is where we start from…” Midway, then, was a turning point, but by no means were the leaders of Japan and Germany ready to throw in the towel.

Moreover, the real nature of the Battle of Midway was poorly understood for some months after the Japanese defeat. On 9 June 1942, The New York Times noted that,

So far as we can now learn, the main damage to the Japanese fleet off Midway was inflicted by our land-based airplanes. The battle shows what land-based air power can do to naval and air power attacking from the open sea when that land-based air power is alert, well-trained, courageous, and exists in sufficient quantity…

But this was dead wrong. The Army Air Force B-17s and B-26s did not achieve one hit on the Japanese carriers. The pilots, not accustomed to attacks on ships, had perceived hits when there were none. Despite their courage and tenacity, they had missed the enemy carriers. The really effective attacks were made by the carrier dive bombers.

The proof of this came on 19- 20 June 1944, in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. You might think of this as “The Battle of Midway, Round Two.” Fought near the island of Saipan in the Marianas group, the Battle of the Philippine Sea set the rebuilt Japanese carrier force, commanded by Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, against Admiral Spruance’s Fifth Fleet. Both navies had studied the Battle of Midway, and both had learned from it, but it was only the U.S. Navy that had created a carrier force that could advance deep into enemy territory and defeat both land-based and carrier-based air forces. In two days of multiple air battles, the Japanese lost over 90 percent of the aircraft that they had thrown against Spruance’s carriers and surface ships. Philippine Sea was the “last gasp” of the Japanese fleet’s carrier aviators. At the end of October 1944, after its defeat at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Japanese navy began using kamikaze (suicide) attacks in an effort to compensate for the defeat of its carrier forces.

What gave the U.S. forces their great victory at Midway? One critical factor was communications intelligence. Admiral Nimitz, Pacific Fleet commander, had clear warning of the objective of the Japanese forces and their timing. He knew where the Japanese carrier forces would come from and when they would most likely attack, and he was able to position the three American aircraft carriers to ambush the Japanese. Another critical factor was the ability of Navy aviators to seize an advantage when they found it. American air forces had attacked the Japanese carriers piecemeal on 4 June 1942. The initial attacks had all failed to destroy or damage any of the four Japanese carriers. But fortuitously two squadrons of Navy dive bombers arrived over three of the Japanese carriers when the Japanese defensive fighters had been distracted by the earlier attacks. The dive bombers so seriously damaged those three carriers that all three had to be abandoned. It was, as the historian Walter Lord put it, an “incredible victory,” but it was also something that the U.S. Navy’s carrier aviators had planned and trained for.

Further reading:

The Japanese side of the Battle of Midway is told in Shattered Sword, The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005). A good book on carrier Yorktown in the battle is That Gallant Ship: USS Yorktown (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories, 1985), by Navy historian Robert Cressman. The late Gordon W. Prange (with Donald Goldstein and Katherine Dillon) wrote a history of the battle entitled Miracle at Midway (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1982), and there is also the book that I edited, The Battle of Midway (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013), which has excerpts from a number of accounts and interpretations of the battle. In addition, the Navy’s World War II historian, Professor Samuel Eliot Morison of Harvard, wrote Volume IV of his History of United States Naval Operations in World War II on “Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, May 1942-August 1942” (Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co., 1960).

Tom Hone is a retired member of the Naval War College faculty and a former senior executive in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He is the author or co-author of six books.